isolator

(1) Work slowly. Think of ways to in crease the number of movements necessary on your job: use a light hammer instead of a heavy one, try to make a small wrench do when a big one is necessary, use little force where considerable force is needed, and so on.

(...)

(8) If possible, join or help organize a group for presenting employee problems to the management. See that the procedures adopted are as inconvenient as possible for the management, involving the presence of a large number of employees at each presentation, entailing more than one meeting for each grievance, bringing up problems which are largely imaginary, and so on.

excerpt from the Simple Sabotage Field Manual

It's 10:45. We are taking the train from New Haven's Union Station to New York's Grand Central for a somewhat mandatory workshop as part of my Graphic Design MFA at Yale. Half of my class has a cold today. I have a hangover. Aside from the droning AC, it's silent. We're all staring at the same PDF on our phones, trying to absorb something from the text before the train arrives. I'm too exhausted to read theory. But I brought my laptop. Somehow the idea of wasting time while commuting scares me. I decide to clean up my desktop. My obsessive organization prevents this from being a real-time filler. But right now, I'll take anything that makes me feel productive.

While sorting the PDFs, I come across an article from the New York Times Magazine that I found probably found on Are.na. It's by Kyle Chayka titled "How Nothingness Became Everything We Wanted," which I deem destiny. His website mentions a book he wrote on the same subject titled The Longing For Less, which Jenny Odell previewed as "revealing something surprising and thoroughly alive". For Jia Tolentino, he "arrives not as an addition to the minimalist canon but as a corrective to it.” It's more than an hour until we get to New York, and with every stop, I feel closer to unconsciousness. I've taken this train so often but every time it feels like another random congregation of buildings in New England has been added to the route as a mandatory stop. According to the audio version the piece takes half an hour. I'm a slow reader. The thing goes down like butter in bullet-proof coffee. Once I'm done we arrive at Grand Central.

Chayka's piece is a joyride through the ins and outs of minimalist consumerism, a vivid, (kaleidoscopic?) account of what he started calling the culture of negation. Here is the pitch. The demands, noise, and complexities of contemporary (big-city) work-life are too much to handle. To maintain some sense of self, we escape, refuse, isolate—willingly or not—from the all-around madness. We start with Chayka's experience as a customer in the float tank industry. Floating is just one of the many wellness trends that have been "pitched to prey upon our collective anxiety". After his floating session, he sees it everywhere.

There are moments when it feels as though the universe is trying to send you a message, the vibration of a particular wavelength driving a possibly justified paranoia. Signs of a culture-wide quest for self-obliteration appeared everywhere in the time after my first float.

This desire for nothingness manifests not only in sensory deprivation tanks but in anything from succulents, Japanese ceramics, Uniqlo, Athleisure, cashmere sweaters, slugging, CBD oil, Soylent, Vapes, and White Claw, to existential memes, LSD, Ketamine and Tiger King. Domestic Cozy also get's an honorary mention. For Chayka, all this stuff is a sign of the culture of negation and this culture stands for a (US American) obsession with absence and a failure of optimism. Because optimism is mandatory this culture is something that we don't truly want. If you believe the comment section Chayka is guilty of that same failure of optimism: There was too little acknowledgement of his own privilege and the therapeutic benefits of self-care and too much attention paid to the engulfing warmths of capitalisms newest temptations.

But there are also two more assigned readings that I had to do for another class. Bear with me. The first by Chayka's aforementioned colleague Jia Tolentino, who left one of the many positive reviews of Chayka's book on his site. She also wrote another piece about the same theme for the New Yorker, The Pitfalls and the Potential of the New Minimalism. We were asked to read her Guardian piece, Athleisure, barre and kale: the tyranny of the ideal woman. It's an excerpt from her 2019 book Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion. The second was the review of Trick Mirror by Lauren Oyler, ominously titled 'Ha ha! Ha ha!'. It generated so much traffic that it crashed The London Review of Books’ website. Consensus in class was that Oyler was too personal in her critique. It's fierce, but personal might be crucial here.

What seems self-evident to me is that public writing is always at least a little bit self-interested, demanding, controlling and delusional, and that it’s the writer’s responsibility to add enough of something else to tip the scales away from herself. For readers hoping to optimise the process of understanding their own lives, Tolentino’s book will seem ‘productive’. But those are her terms. No one has to accept them.

Maybe Chayka's and Tolentino's accounts, with all their supposedly sprawling, delusional, solipsistic attempts to frame anything under a personal theory of everything be read as a symptom of the very issue they are discussing. Tolentino's book has delusion built into the title and Chayka is at least hinting at his 'possibly justified paranoia'. Maybe this culture of negation simply implies focusing on yourself, on your very personal view of how things are. Of course, as we all know, focus doesn't come easy these days.

Paying too much Attention

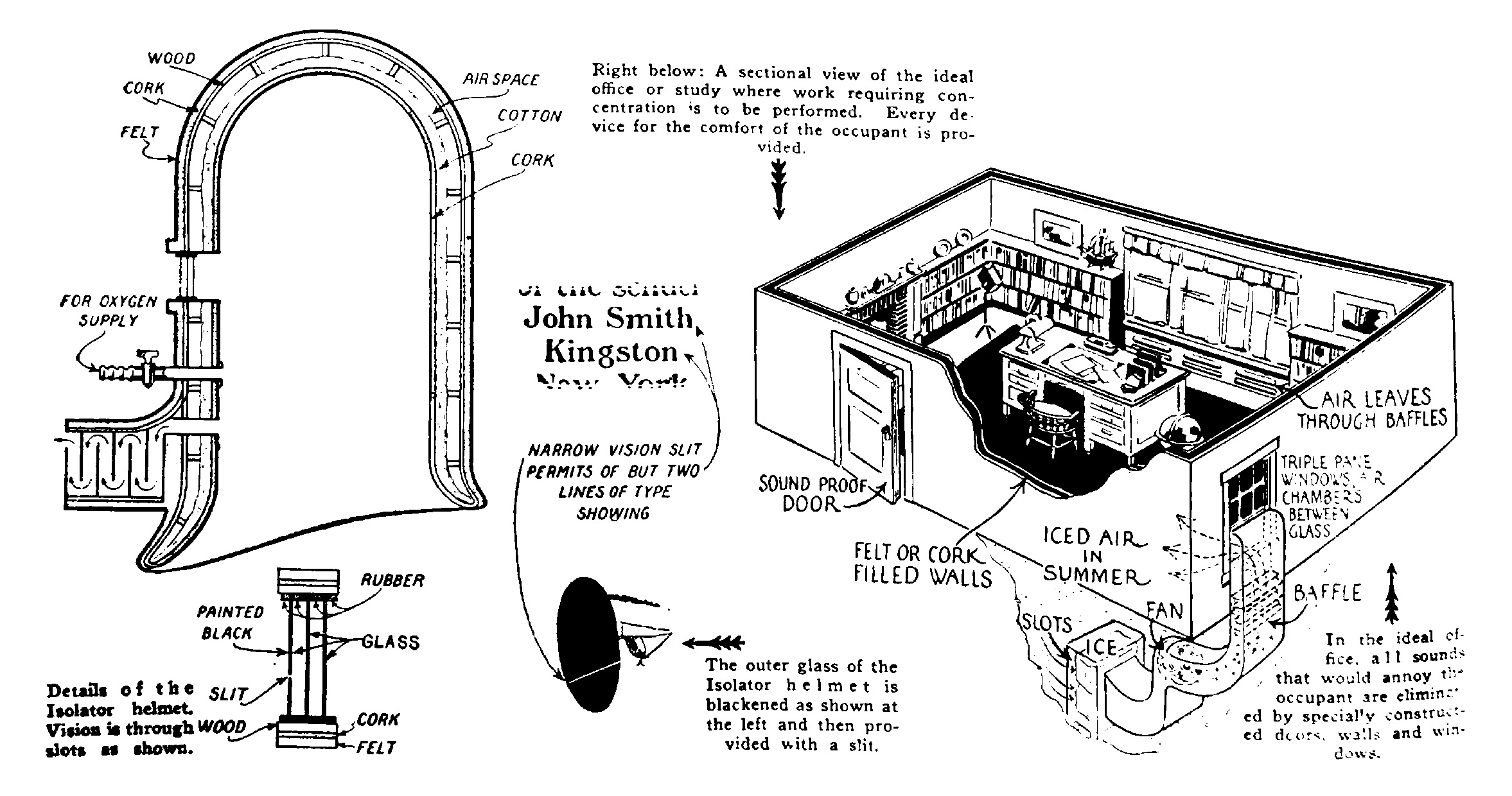

In 1925 Hugo Gernsback, the grandfather of sci-fi had a hard time focusing on his writing. He was sitting in his office, Do not Disturb turned on, and windows shut. But he could still hear so much noise coming from the street. If not that then there would be a telephone ringing, or someone slammed a door. It was unbearable. Even if he was sitting in perfect silence, half the time he started to zone out. He would get lost in the patterns on the tapestry or follow a fly around the room. Hugo needed help. Ritalin was only synthesized in 1944 and since he was an inventor, he came up with a device. He called it The Isolator, a sensory deprivation helmet made of wood, cork and felt, equipped with a pair of goggles that were completely blacked out except for two slits to see the current line of his writing. You have probably seen it on Netflix. The helmet turned out to be quite stuffy so he hooked it up to an oxygen tank. In combination with the ideal (soundproofed, air-conditioned) office, the Isolator would allow for distraction-free thinking. Problem solved.

A couple of years ago I bought an app called iA writer. iA stands for Information Architects and is the name of the company who makes this text processor. iA writer features a 'Focus Mode' that, if activated, only shows you the current sentence in full opacity, all the other ones get greyed out. The rest of the UI is equally geared towards minimalist production standards, all in service to provide a 'focused environment where you can write freely'. Recently iA also added Wiki-Link functionality to 'link your notes. Connect your ideas. Navigate your mind.' I'm sure that if Gernsback would still be alive he would use iA writer.

Wiki-Links are also called transclusion links. Transclusion means including content from one document in another. It's like copy-pasting, but if you change the original, it will automatically update everywhere it's been included. Transclusion was popularized by Ted Nelson in the 60s as part of Xanadu—his eternal vaporware hypertext system. Unlike the system of one-directional hyperlinks we have on the web he envisioned a system of bi-directional links. A link from A to B would automatically include a backlink from B to A. Every piece of information could be connected to every other piece, creating a web of interconnected knowledge. Transclusion was a key part of this vision, allowing content to be reused and combined in new ways, without losing its context or source.

Network Fever

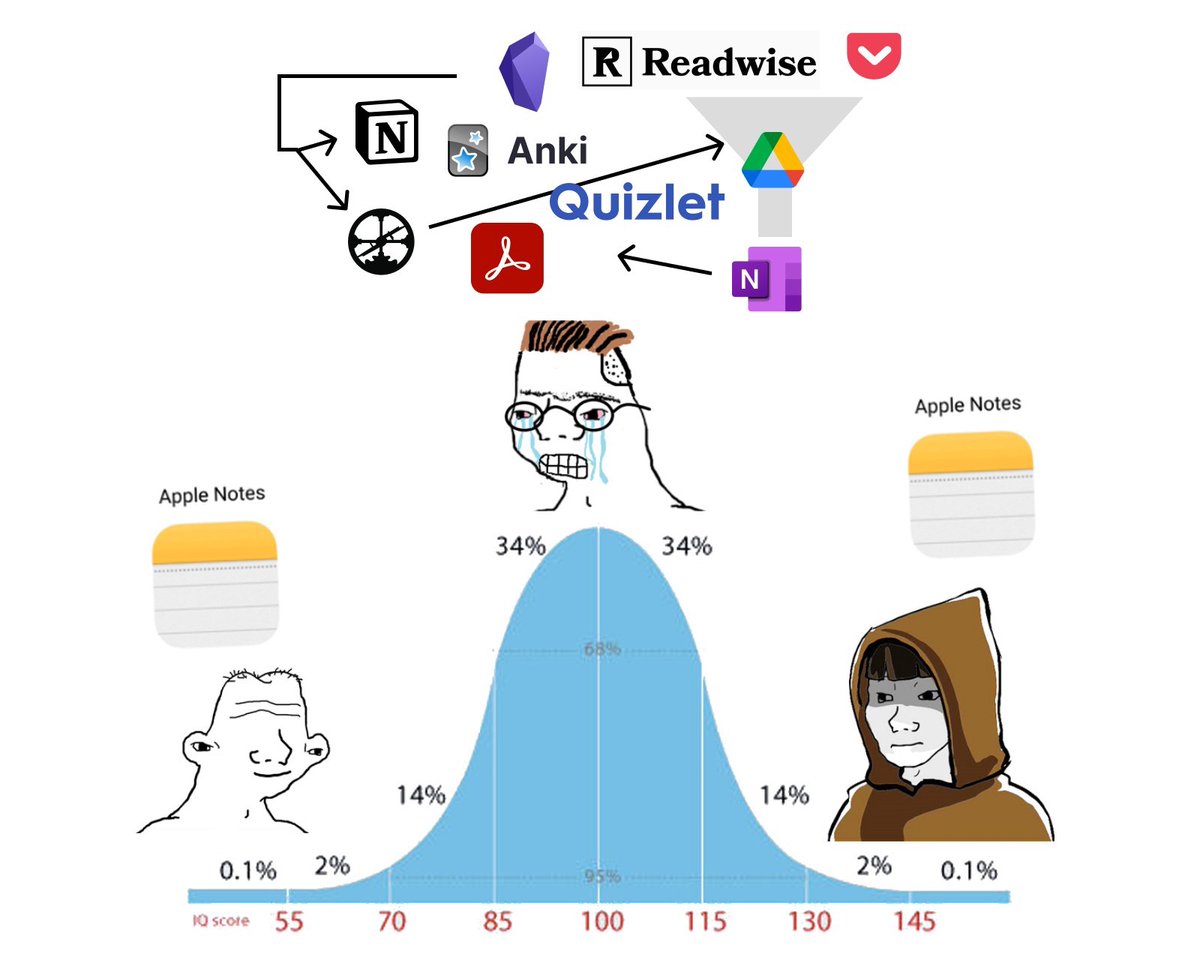

Hyperlinking your notes into a big hairball of knowledge has been pretty hot for a couple of years now (and has been, probably even before Vaneevar Bush dreamed up the Memex). Apps promising to help you make sense of the chaos come in all shapes and sizes, but basically, any text processor that's part of the PKM craze allows you to string your thoughts together, into an observable network of knowledge. On the app-guided path to enlightenment, our obsession with productivity and our desire for serenity converges. Many of these tools have a heavy dose of early internet optimism sprinkled on top. Of course, I have also been tempted to move back to the land to grow a second brain inside my knowledge garden and have since migrated from iA writer to yet another note-taking app.

I'm now using Obsidian—because it's as sophisticated as a blade made from volcanic rock! Obsidian also sports transclusion-link capabilities. Like any tool for thought it also allows you to visualize your connections in a knowledge graph. For the diligent notetaker, the knowledge graph is what followers (social-graphs) are for influencers. The greater the intricacy of your graph, the more edges connecting verts, the more it reflects your impressive cognitive prowess. But as shown in the tweet above personal knowledge management has already been declared a crutch. Unfortunately even the most sophisticated tools won't do the thinking, yet.

In his piece for Real Life Mag, Robert Minto recounts his misadventures in note-taking, trying to build a Zettelkasten a la Niklas Luhmann. He suggests that not only can 'smart' note-taking end in severe procrastination that ultimately ends up disrupting thought but also that 'creating an overly comprehensive portrait of your own thoughts can amount to locking yourself in a labyrinth of your own preconceptions.' This is the law of the instrument: If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail. Perhaps those are simply the nauseating affordances of the world perceived as hypertext. Everything that can be connected will be connected. The term for this is 'network fever'. It's coined by Mark Wigley and in his book 'A Prehistory of the Cloud' the scholar Tung-Hui Hui describes it like this.

Network fever is the desire to connect all networks, indeed, the desire to connect every piece of information to another piece. And to construct a system of knowledge where everything is connected is, as psychoanalysis tells us, the sign of paranoia.

In other words, network fever cann´é separated from the network, because the network is its fever. The cloud like nature of the network has much less to do with its structural or technological properties than the way that we perceive and understand it; seen properly, the cloud resides within us.

All that brain fog blurs the distinction between fact and fiction. While thinking in isolation soothes the desire to disentangle the chaos, it also fuels the network fever. Thats the price of paying a little too much attention to paying attention. Maybe such suspicions are more symptomatic of the buzz that kicks in when floating in epsom salt or when suspended in a network of ideas inside my note-taking app. Either way it helps to remember how you are interfacing with the world. But in turn this also means that if you crank the radar up to eleven, you will likely start seeing Chinese weather balloons everywhere. Maybe that's just my opinion. Dominic Tarr—the programmer behind the peer to peer network protocol Scuttlebutt—once neatly tweeted: 'Distinguishing between facts and other people's opinions is easy, but distinguishing between facts and your own opinions, much harder.' Luckily I don't have to rely on just myself. As Oyler noted I can always add something else. After all the best antidote to the maddening silence of isolation might as well be the noise of other people's opinions.

On our way back from New York, we were drinking on the train. It has always seemed counterintuitive that you are not allowed to drink in public, but you can drink on a train. It was lively. The person sitting in the booth next to us turned around and gave us a stare-down. Then they yelled, "CAN YOU LOWER YOUR VOICE?" No one knew how to respond. Before we could think of a clever reply, someone sitting next to us put them in their place: "This is bullshit! This is not a quiet car!"

Suddenly I had all these ideas. I pulled out my phone to take a note of what just happened. I wanted to write something about the train ride as a literal connection between two nodes in a network. I would also weave in something about social media, the digital commons and the need for public spaces. But when I opened Obsidian, I accidentally tapped the graph view icon, and there they were all my notes. So beautifully disconnected and isolated from each other, full of potential, like a painting made in a desert of knowledge.